One Dataset to rule them All.

The databases released by ICIJ contain information on:

- The Offshore Leaks: 130 000 offshore accounts disclosed in a report (2013)

- The Panamas Papers: 214 000 offshore accounts from Mossack Fonseca, as presented above (2016)

- The Bahamas Leaks: 1.3 million internal files from the company register of the Bahamas (2016)

- The Paradise Papers: 13.4 million electronic documents relating to offshore investments (2017)

This database is powered by Neo4j, a graph database that structures data in nodes and edges. The data was downloaded as several CSV files, one for each actor type and one for the links between them. The different nodes represent:

- The offshore entity: a company created in a low-tax jurisdiction that often attracts non-resident client through preferential tax treatment

- The officer: a person or company who plays a role in an offshore entity

- The intermediary: a go-between for someone seeking an offshore corporation and an offshore service provider (usually a law firm)

- The address: a contact postal address as it appears in the original database

In total, this database contains information about more than 785 000 offshore entities and links to people and companies in more than 200 countries. Note that this data comes from leaked records and not a standardized corporate registry, so there may be duplicates (as similar appearances were not merged).

No cleaning or standardization was necessary (see ICIJ site for more details).

Before investigating the charities, we can explore the dataset and the offshore companies to have a more general view of the situation. We were particularly interested in the Panamas Papers dataset. How were the offshore companies distributed around the world? How many countries sheltered these 200 000 companies?

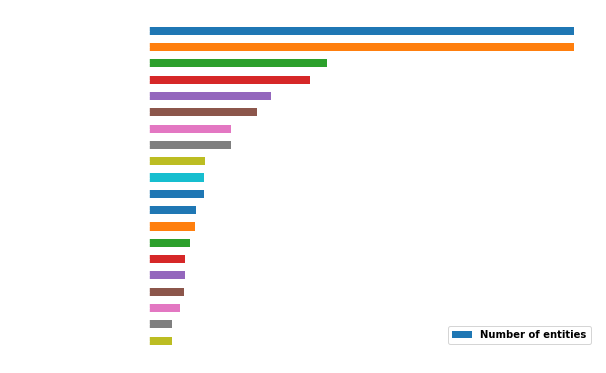

We were not surprised to see that majority of our entities were located in a small number of countries. Indeed, half of the countries quoted in the dataset put together contain only a few of the total number of offshore companies.

Note the presence of the United Kingdom in the top 10; the UK is strongly appreciated by entrepreneurs and companies for the possible UK non-domiciled status that enables actors to avoid taxes on foreign income.

In conclusion, there was no particular surprise with this top 20, each country being a well-known tax haven. As a whole, this leads to a non-uniform geographic distribution.

But now let's take a closer look at our charities! We need first to find them in the database. Since no detail was given in the dataset about the different companies' functions, we need external data to help our investigation.

We chose to use Forbes Magazine's list of the top 100 richest US charities, as well as Wikipedia's lists of main non-governmental organizations and main charitable foundations. We scraped these websites in order to form a new dataset of well-known charities. By merging together these results, we obtained detailed information on more than 300 charities that we could use to investigate the ICIJ database. Collected details about charities include names, leaders, headquarters addresses and locations of major offices. Note that the available data varies from charity to charity, resulting in a sometimes sparse dataset.

We decided to isolate potential charities in the Panama Papers by their name. We considered an offshore company to be a potential match for a charity when its name was closely related to that of one of the scraped charitable foundations. This was achieved by text mining, where our algorithm matched word sequences based on a percentage of common significative words. Using this method, we reduced the dataset from hundreds of thousands of entities to a few hundred names.

Considering the reasonable number of matches and since humans possess an expertise in natural language processing superior to any training tool, we inspected and corrected the potential matches manually.

Among the matches, we found Amnesty International, the International Red Cross, and many others of the world's biggest aid agencies.